[1] Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5210

[2] Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39(1):16-25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107

[3] Knutsson A, Kempe A. Shift work and diabetes – a systematic review. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31(10):1146-51. doi: 0.3109/07420528.2014.957308

[4] Wagstaff AS, Sigstad Lie JA. Shift and night work and long working hours--a systematic review of safety implications. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(3):173-85. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3146

[5] Wang X, Armstrong M, Cairns B, Key T, Travis R. Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup Med. 2011;61(2):78-89. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr001

[6] Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the Nurses' Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:825-88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.11.825

[7] Papantoniou K, Devore EE, Massa J, Strohmaier S, Vetter C, Yang L, et al. Rotating night shift work and colorectal cancer risk in the nurses’ health studies. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(11):2709-17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31655

[8] Åkerstedt T, Knutsson A, Narusyte J, Svedberg P, Kecklund G, Alexanderson K. Night work and breast cancer in women: a Swedish cohort study. BMJ open. 2015;5(4):e008127. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008127

[9] Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Reinberg A, Sackett-Lundeen L, Portaluppi F. Circadian disruption: New clinical perspective of disease pathology and basis for chronotherapeutic intervention. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(8):1101-19. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2016.1184678

[10] Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Stern N, Bilu C, El-Osta A, Einat H, et al. The Circadian Syndrome: is the Metabolic Syndrome and much more! J Intern Med. 2019;286(2):181-91. doi: 10.1111/joim.12924

[11] World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326814/.

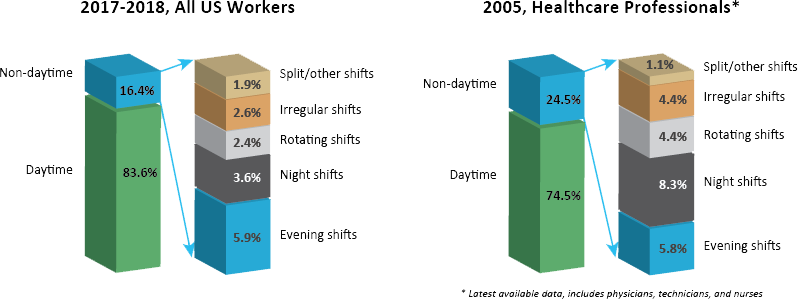

[12] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 7. Workers by shift usually worked and selected characteristics, averages for the period 2017-2018 Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2019 [Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex2.t07.htm.

[13] Job flexibilities and work schedules summary [press release]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, 24 September 2019.

[14] Booker LA, Magee M, Rajaratnam SMW, Sletten TL, Howard ME. Individual vulnerability to insomnia, excessive sleepiness and shift work disorder amongst healthcare shift workers. A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;41:220-33. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.03.005

[15] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 5. Shift usually worked: Full-time wage and salary workers by occupation and industry, May 2004 Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2005 [Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex.t05.htm.

[16] Ngan K, Drebit S, Siow S, Yu S, Keen D, Alamgir H. Risks and causes of musculoskeletal injuries among health care workers. Occup Med. 2010;60(5):389-94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq052

[17] Lee DJ, Fleming LE, LeBlanc WG, Arheart KL, Ferraro KF, Pitt-Catsouphes M, et al. Health status and risk indicator trends of the aging US health care workforce. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(4):497-503. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318247a379

[18] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table 47: Absences from work of employed full-time wage and salary workers by occupation and industry Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2019 [Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat47.htm.

[19] Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Caring for our caregivers: Facts about hospital worker safety Washington, D.C. : Occupational Safety and Health Administration; 2013 [32]. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/dsg/hospitals/documents/1.2_Factbook_508.pdf.

[20] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2019 [updated January 22, 2020. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/tables.htm.

[21] Dressner MA. Hospital workers: An assessment of occupational injuries and illnesses. Mon Labor Rev [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/hospital-workers-an-assessment-of-occupational-injuries-and-illnesses.htm.

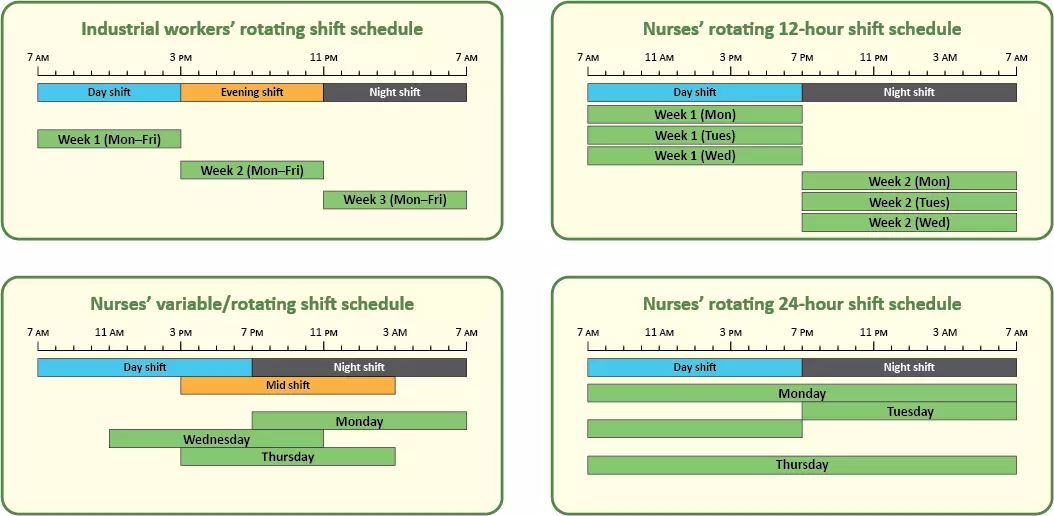

[22] Richardson A, Turnock C, Harris L, Finley A, Carson S. A study examining the impact of 12-hour shifts on critical care staff. J Nurs Manage. 2007;15(8):838-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2007.00767.x

[23] Dwyer T, Jamieson L, Moxham L, Austen D, Smith K. Evaluation of the 12-hour shift trial in a regional intensive care unit. J Nurs Manage. 2007;15(7):711-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00737.x

[24] Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Kawachi I, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women participating in the Nurses' Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(20):1563-8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.20.1563

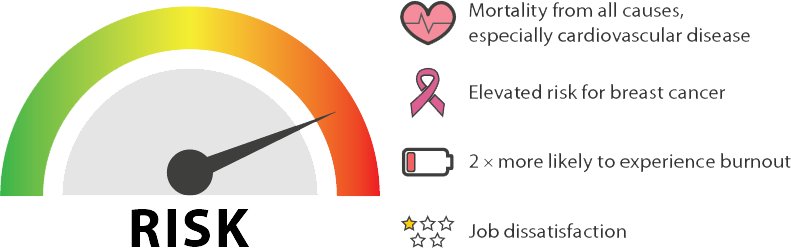

[25] Gu F, Han J, Laden F, Pan A, Caporaso NE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Total and cause-specific mortality of U.S. nurses working rotating night shifts. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(3):241-52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.018

[26] Ferri P, Guadi M, Marcheselli L, Balduzzi S, Magnani D, Di Lorenzo R. The impact of shift work on the psychological and physical health of nurses in a general hospital: A comparison between rotating night shifts and day shifts. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:203-11. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S115326

[27] Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, et al. Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1573-81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2016.303338

[28] Wegrzyn LR, Tamimi RM, Rosner BA, Brown SB, Stevens RG, Eliassen AH, et al. Rotating night-shift work and the risk of breast cancer in the Nurses' Health Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(5):532-40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx140

[29] Hansen J. Night shift work and risk of breast cancer. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2017;4(3):325-39. doi: 10.1007/s40572-017-0155-y

[30] Travis RC, Balkwill A, Fensom GK, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Wang X-S, et al. Night shift work and breast cancer incidence: Three prospective studies and meta-analysis of published studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(12). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw169

[31] Salamanca-Fernández E, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Guevara M, Ardanaz E, Olry de Labry Lima A, Sánchez MJ. Night-shift work and breast and prostate cancer risk: Updating the evidence from epidemiological studies. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2018;41(2):211-26. doi: 10.23938/assn.0307

[32] Dun A, Zhao X, Jin X, Wei T, Gao X, Wang Y, et al. Association between night-shift work and cancer risk: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10(1006). doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01006

[33] Stimpfel AW, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Affairs. 2012;31(11):2501-9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1377

[34] American Nurses Association. Healthy Nurse Healthy Nation: Year Two Highlights, 2018-2019. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2019. Available from: https://www.healthynursehealthynation.org/globalassets/all-images-view-with-media/about/2019-hnhn_highlights.pdf.

[35] Shockey TM, Wheaton AG. Short Sleep Duration by Occupation Group — 29 States, 2013–2014. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2017;66(8):207–13. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a2.

[36] Chang W-P, Li H-B. Differences in workday sleep fragmentation, rest-activity cycle, sleep quality, and activity level among nurses working different shifts. Chronobiol Int. 2019;36(12):1761-71. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2019.1681441

[37] Weaver MD, Vetter C, Rajaratnam SMW, O’Brien CS, Qadri S, Benca RM, et al. Sleep disorders, depression and anxiety are associated with adverse safety outcomes in healthcare workers: A prospective cohort study. J Sleep Res [Internet]. 2018; 27(6):[e12722 p.]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jsr.12722.

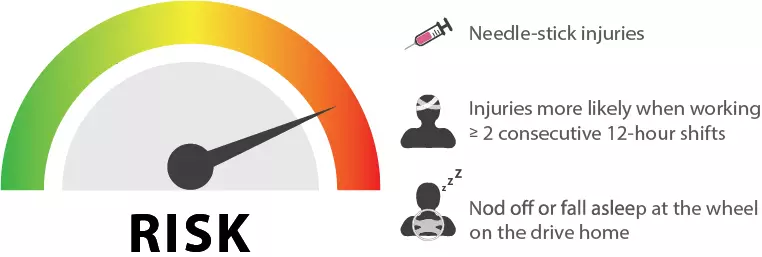

[38] Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, J. L. Work schedule, needle use, and needlestick injuries among registered nurses. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28(2):156-64. doi: 10.1086/510785

[39] Hopcia K, Dennerlein JT, Hashimoto D, Orechia T, Sorensen G. Occupational injuries for consecutive and cumulative shifts among hospital registered nurses and patient care associates: A case-control study. Workplace Health & Safety. 2012;60(10):437-44. doi: 10.1177/216507991206001005

[40] Stimpfel AW, Brewer CS, Kovner CT. Scheduling and shift work characteristics associated with risk for occupational injury in newly licensed registered nurses: An observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(11):1686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.06.011

[41] Gold DR, Rogacz S, Bock N, Tosteson TD, Baum TM, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating shift work, sleep, and accidents related to sleepiness in hospital nurses. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(7):1011-4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.7.1011

[42] Novak RD, Auvil-Novak SE. Focus group evaluation of night nurse shiftwork difficulties and coping strategies. Chronobiol Int. 1996;13(6):457-63. doi: 10.3109/07420529609020916

[43] Scott LD, Hwang WT, Rogers AE, Nysse T, Dean GE, Dinges DF. The relationship between nurse work schedules, sleep duration, and drowsy driving. Sleep. 2007;30(12):1801-7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1801

[44] Ftouni S, Sletten TL, Howard M, Anderson C, Lenné MG, Lockley SW, et al. Objective and subjective measures of sleepiness, and their associations with on-road driving events in shift workers. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(1):58-69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01038.x

[45] Mulhall MD, Sletten TL, Magee M, Stone JE, Ganesan S, Collins A, et al. Sleepiness and driving events in shift workers: the impact of circadian and homeostatic factors. Sleep. 2019;42(6). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz074

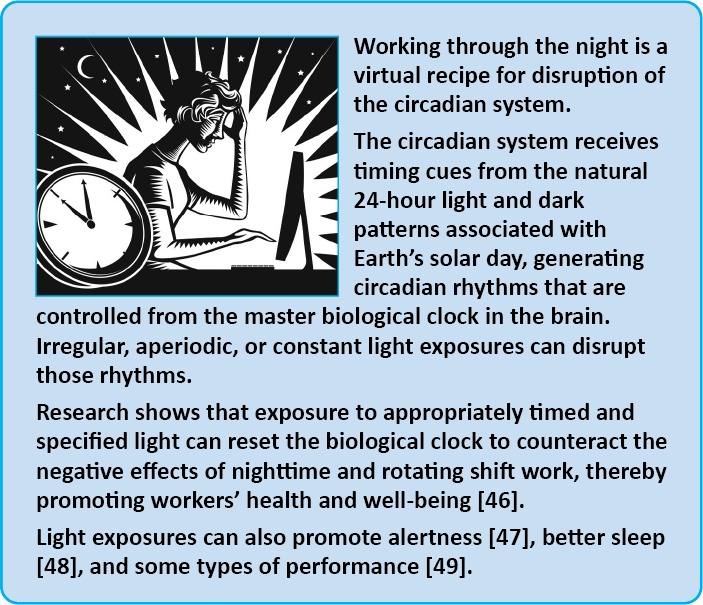

[46] Neil-Sztramko SE, Pahwa M, Demers PA, Gotay CC. Health-related interventions among night shift workers: a critical review of the literature. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(6):543-6. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3445

[47] Figueiro MG, Sahin L, Wood B, Plitnick B. Light at night and measures of alertness and performance: Implications for shift workers. Biol Res Nurs. 2016;18(1):90-100. doi: 10.1177/1099800415572873

[48] Boivin DB, Boudreau P, James FO, Kin NM. Photic resetting in night-shift work: impact on nurses' sleep. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(5):619-28. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.675257

[49] Tanaka K, Takahashi M, Tanaka M, Takanao T, Nishinoue N, Kaku A, et al. Brief morning exposure to bright light improves subjective symptoms and performance in nurses with rapidly rotating shifts. Journal of occupational health. 2011;53(4):258-66. doi: 10.1539/joh.L10118

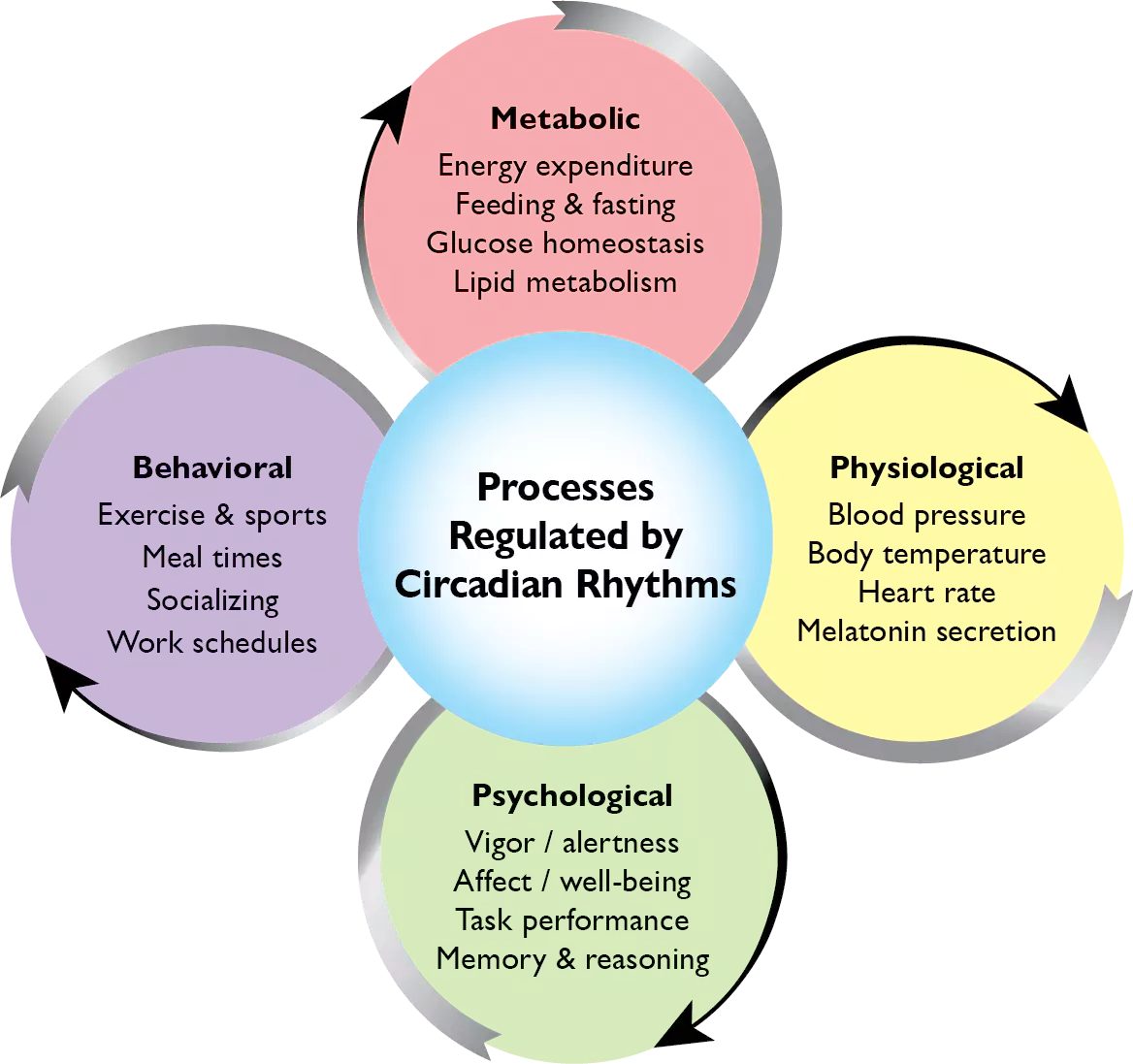

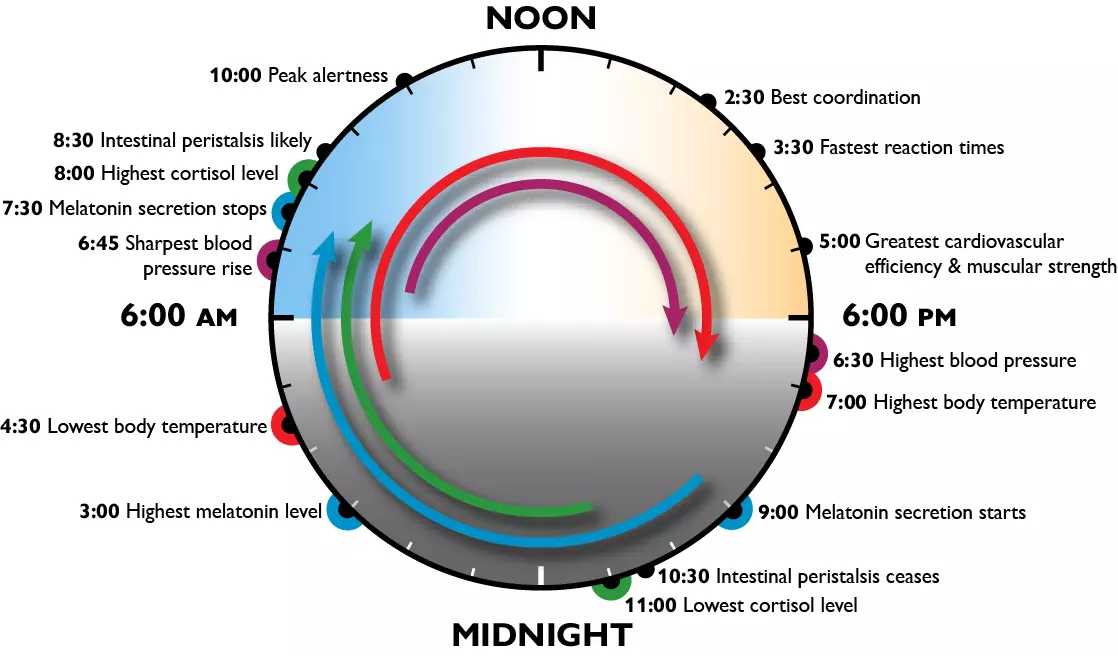

[50] Turek FW. Circadian clocks: Not your grandfather's clock. Science. 2016;354(6315):992-3. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2613

[51] Sollars PJ, Pickard GE. The neurobiology of circadian rhythms. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015;38(4):645-65. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2015.07.003

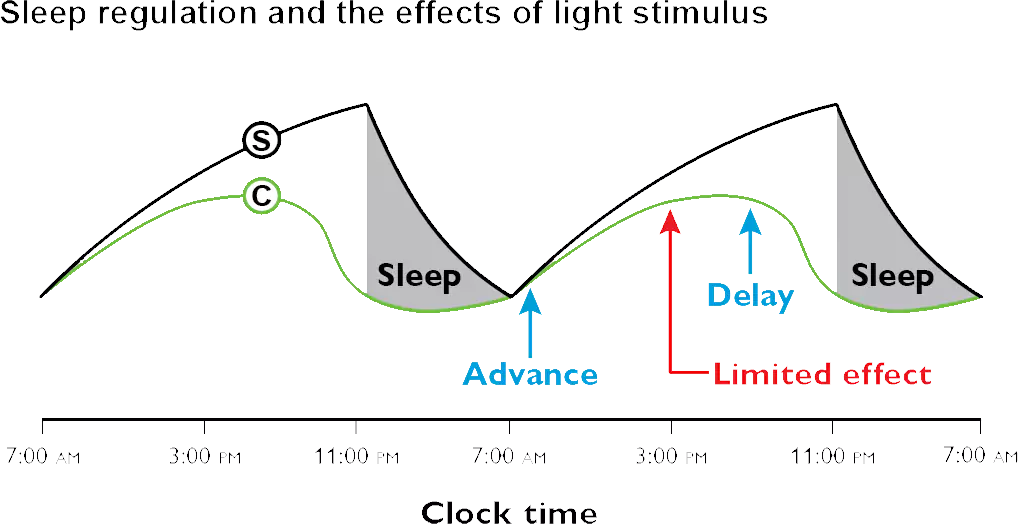

[52] Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Effect of light on human circadian physiology. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4(2):165-77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.01.004

[53] Czeisler CA, Gooley JJ. Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Humans. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 2007; 72:579-97. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.064

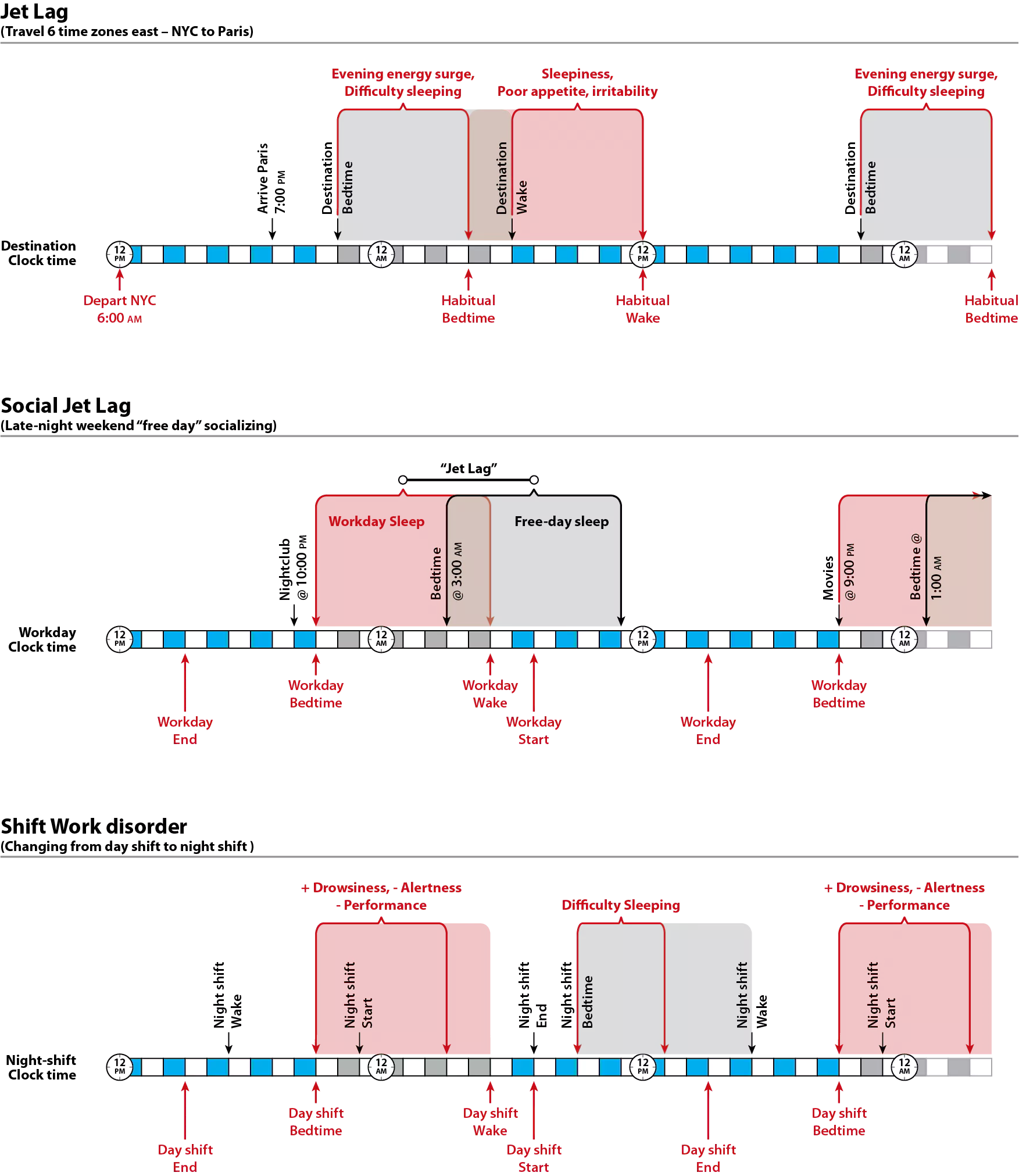

[54] Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Carrier J, Kupfer DJ. Inducing jet-lag in older people: Directional asymmetry. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(2):101-16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00184.x

[55] Sack RL. The pathophysiology of jet lag. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2009;7(2):102-10. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.006

[56] Jankowski KS. Social jet lag: Sleep-corrected formula. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(4):531-5. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1299162

[57] Wright KP, Jr., Bogan RK, Wyatt JK. Shift work and the assessment and management of shift work disorder (SWD). Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(1):41-54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.02.002

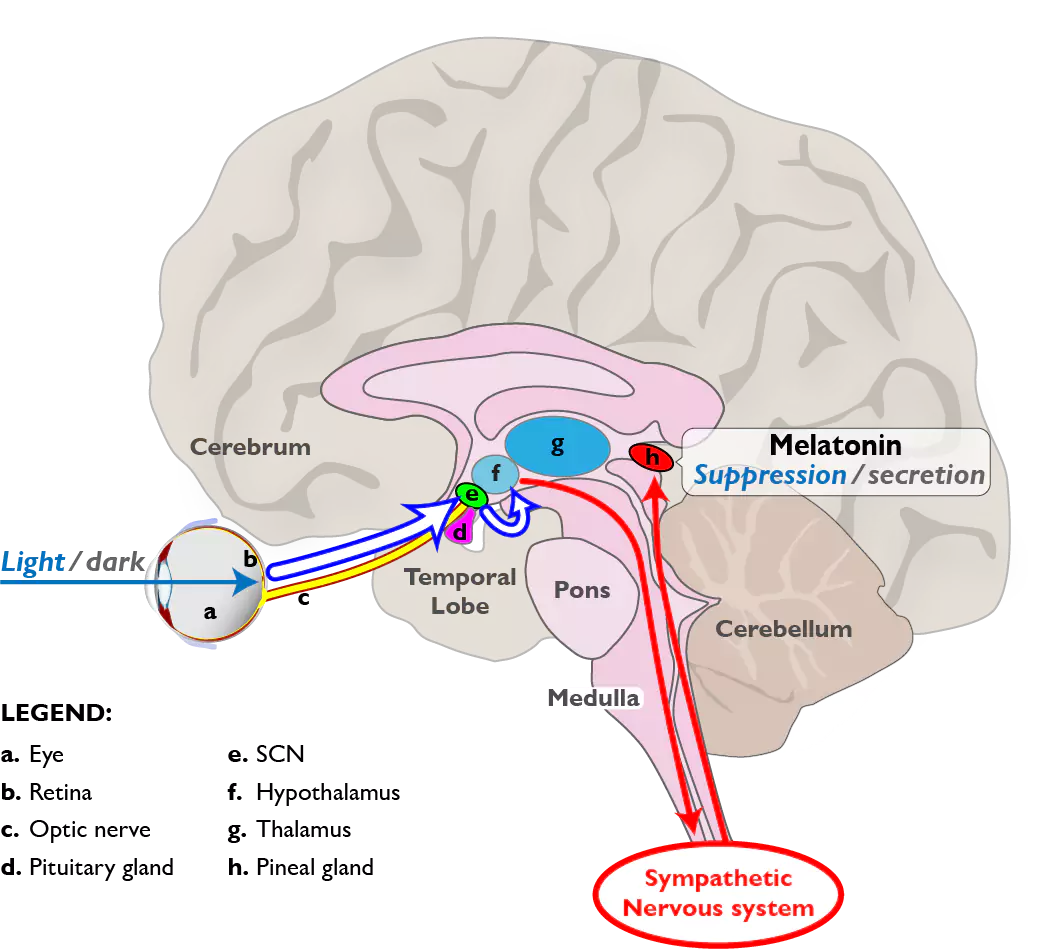

[58] Gooley JJ, Lu J, Chou TC, Scammell TE, Saper CB. Melanopsin in cells of origin of the retinohypothalamic tract. Nature neuroscience. 2001;4(12):1165-. doi: 10.1038/nn768

[59] Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science. 2002;295(5557):1070-3. doi: 10.1126/science.1067262

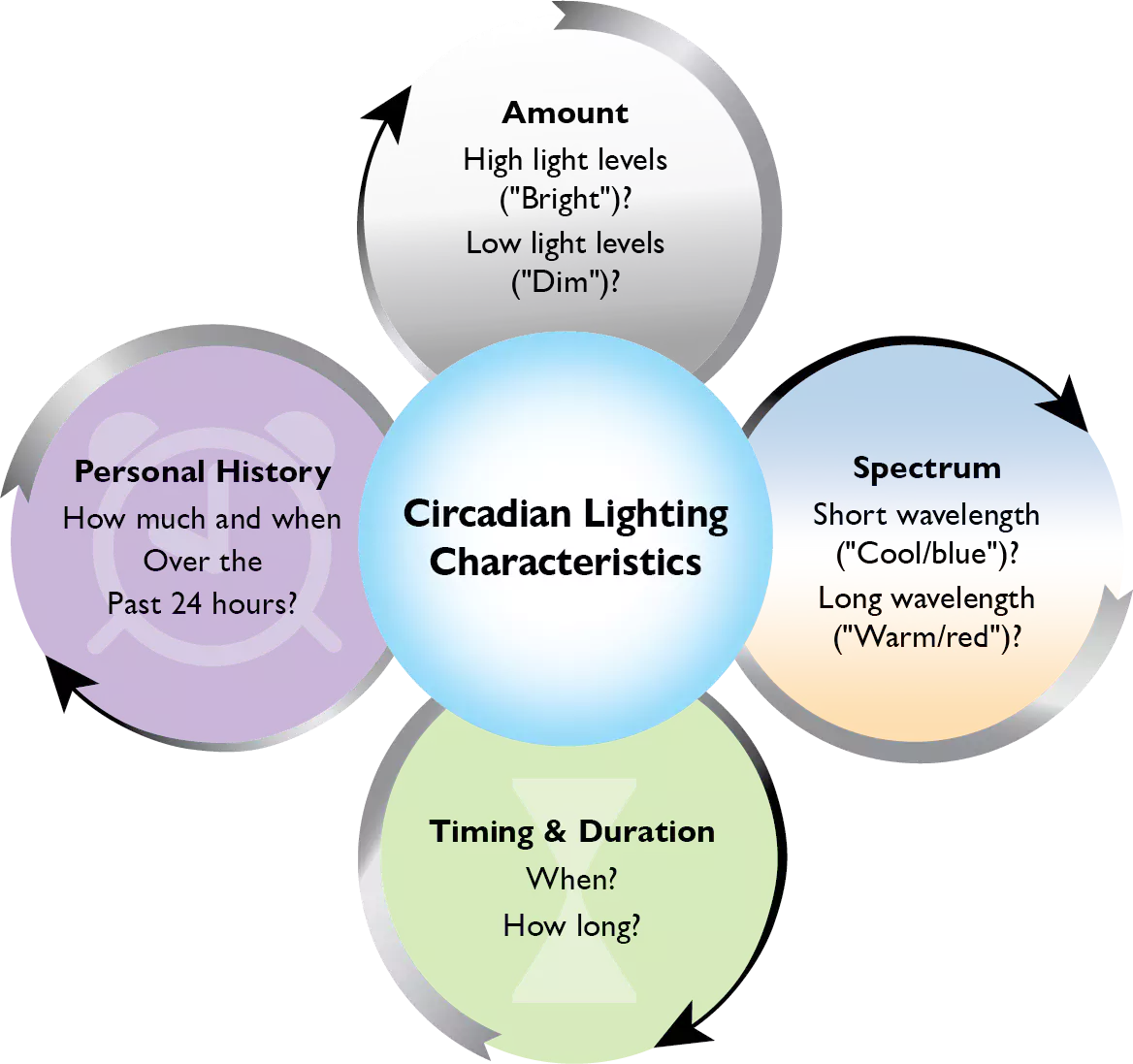

[60] Rea MS, Figueiro MG, Bullough JD. Circadian photobiology: An emerging framework for lighting practice and research. Lighting Res Technol. 2002;34(3):177-87. doi: 10.1191/1365782802lt057oa

[61] Czeisler CA, Shanahan TL, Klerman EB, Martens H, Brotman DJ, Emens JS, et al. Suppression of melatonin secretion in some blind patients by exposure to bright light. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;332(1):6-11. doi:

[62] Panda S, Provencio I, Tu DC, Pires SS, Rollag MD, Castrucci AM, et al. Melanopsin is required for non-image-forming photic responses in blind mice. Science. 2003;301(5632):525-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1086179

[63] Cassone VM, Warren WS, Brooks DS, Lu J. Melatonin, the pineal gland, and circadian rhythms. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8 Suppl:S73-81. doi: 10.21236/ada250640

[64] Lunn RM, Blask DE, Coogan AN, Figueiro MG, Gorman MR, Hall JE, et al. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: A report on the National Toxicology Program's workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci Total Environ. 2017;607-608:1073-84. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.056

[65] Reutrakul S, Knutson KL. Consequences of Circadian Disruption on Cardiometabolic Health. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(4):455-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.07.005

[66] Salgado-Delgado R, Tapia Osorio A, Saderi N, Escobar C. Disruption of circadian rhythms: A crucial factor in the etiology of depression. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:839743-. doi: 10.1155/2011/839743

[67] Czeisler CA, Klerman EB. Circadian and sleep-dependent regulation of hormone release in humans. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1999;54:97-132. doi:

[68] Pandi-Perumal SR, Smits M, Spence W, Srinivasan V, Cardinali DP, Lowe AD, et al. Dim light melatonin onset (DLMO): A tool for the analysis of circadian phase in human sleep and chronobiological disorders. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.06.020

[69] Jung CM, Khalsa SBS, Scheer FAJL, Cajochen C, Lockley SW, Czeisler CA, et al. Acute Effects of Bright Light Exposure on Cortisol Levels. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25(3):208-16. doi: 10.1177/0748730410368413

[70] Stawski RS, Almeida DM, Lachman ME, Tun PA, Rosnick CB, Seeman T. Associations between cognitive function and naturally occurring daily cortisol during middle adulthood: timing is everything. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2011;66 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i71-i81. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq094

[71] Jentsch VL, Merz CJ, Wolf OT. Restoring emotional stability: Cortisol effects on the neural network of cognitive emotion regulation. Behav Brain Res. 2019;374:111880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.03.049

[72] Pruessner JC, Wolf OT, Hellhammer DH, Buske-Kirschbaum A, von Auer K, Jobst S, et al. Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sci. 1997;61(26):2539-49. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01008-4

[73] Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Adam EK, Pruessner JC, Wüst S, et al. Assessment of the cortisol awakening response: Expert consensus guidelines. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:414-32. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.010

[74] Morris CJ, Aeschbach D, Scheer FAJL. Circadian system, sleep and endocrinology. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;349(1):91-104. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.003

[75] Figueiro MG, Rea MS. Short-wavelength light enhances cortisol awakening response in sleep-restricted adolescents. International journal of endocrinology. 2012;2012:301935. doi: 10.1155/2012/301935

[76] Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Kirschbaum C, Marmot M, Steptoe A. Differences in cortisol awakening response on work days and weekends in women and men from the Whitehall II cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(4):516-28. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00072-6

[77] Fries E, Dettenborn L, Kirschbaum C. The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009;72(1):67-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.014

[78] Wetherell MA, Lovell B, Smith MA. The effects of an anticipated challenge on diurnal cortisol secretion. Stress. 2015;18(1):42-8. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.993967

[79] Dawson D, Campbell SS. Bright light treatment: are we keeping our subjects in the dark? Sleep. 1990;13:267-71. doi: 10.1093/sleep/13.3.267

[80] Daurat A, Foret J, Benoit O, Mauco G. Bright light during nighttime: effects on the circadian regulation of alertness and performance. Biological Signals and Receptors. 2000;9(6):309-18. doi: 10.1159/000014654

[81] Cajochen C, Zeitzer JM, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ. Dose-response relationship for light intensity and ocular and electroencephalographic correlates of human alertness. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115(1):75-83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00236-9

[82] Badia P, Myers B, Boecker M, Culpepper J, Harsh JR. Bright light effects on body temperature, alertness, EEG and behavior. Physiology and Behavior. 1991;50(3):583-8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90549-4

[83] Zeitzer JM, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, Brown EN, Czeisler CA. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: Melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol. 2000;526(Pt3):695-702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x

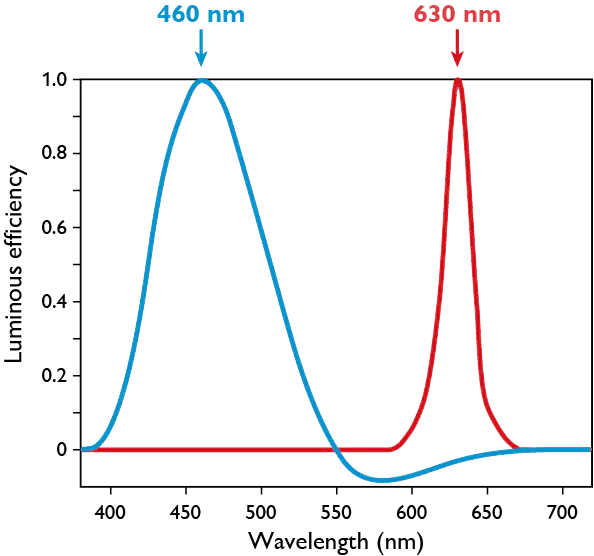

[84] Brainard GC, Hanifin JP, Greeson JM, Byrne B, Glickman G, Gerner E, et al. Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):6405-12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06405.2001

[85] Thapan K, Arendt J, Skene DJ. An action spectrum for melatonin suppression: Evidence for a novel non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor system in humans. J Physiol. 2001;535:261-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00261.x

[86] Cajochen C, Munch M, Kobialka S, Krauchi K, Steiner R, Oelhafen P, et al. High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1311-6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0957

[87] Figueiro MG, Bullough JD, Bierman A, Fay CR, Rea MS. On light as an alerting stimulus at night. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 2007;67(2):171-8. doi:

[88] Sahin L, Figueiro MG. Alerting effects of short-wavelength (blue) and long-wavelength (red) lights in the afternoon. Physiology and Behavior. 2013;116-117:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.014

[89] Smolders KC, de Kort YA, Cluitmans PJ. A higher illuminance induces alertness even during office hours: Findings on subjective measures, task performance and heart rate measures. Physiology and Behavior. 2012;107(1):7-16. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.028

[90] Rüger M, Gordijn MC, Beersma DG, de Vries B, Daan S. Time-of-day-dependent effects of bright light exposure on human psychophysiology: Comparison of daytime and nighttime exposure. American Journal of Physiology. 2006;290(5):R1413-20. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00121.2005

[91] Phipps-Nelson J, Redman JR, Dijk DJ, Rajaratnam SM. Daytime exposure to bright light, as compared to dim light, decreases sleepiness and improves psychomotor vigilance performance. Sleep. 2003;26(6):695-700. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.695

[92] Vandewalle G, Balteau E, Phillips C, Degueldre C, Moreau V, Sterpenich V, et al. Daytime light exposure dynamically enhances brain responses. Current Biology. 2006;16(16):1616-21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.031

[93] Vandewalle G, Schmidt C, Albouy G, Sterpenich V, Darsaud A, Rauchs G, et al. Brain responses to violet, blue, and green monochromatic light exposures in humans: prominent role of blue light and the brainstem. PloS one. 2007;2(11):e1247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001247

[94] Van de Werken M, Gimenez MC, de Vries B, Beersma DG, Gordijn MC. Short-wavelength attenuated polychromatic white light during work at night: limited melatonin suppression without substantial decline of alertness. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(7):843-54. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.773440

[95] Papamichael C, Skene DJ, Revell VL. Human nonvisual responses to simultaneous presentation of blue and red monochromatic light. J Biol Rhythms. 2012;27(1):70-8. doi: 10.1177/0748730411431447

[96] Lok R, Smolders KCHJ, Beersma DGM, de Kort YAW. Light, alertness, and alerting effects of white light: A literature overview. J Biol Rhythms. 2018;33(6):589-601. doi: 10.1177/0748730418796443

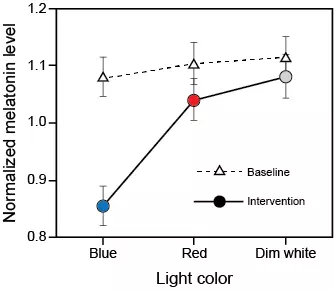

[97] Figueiro MG, Bierman A, Plitnick B, Rea MS. Preliminary evidence that both blue and red light can induce alertness at night. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-105

[98] Sahin L, Wood B, Plitnick B, Figueiro MG. Daytime light exposure: Effects on biomarkers, measures of alertness, and performance. Behav Brain Res. 2014;274:176-85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.017

[99] Goel N, Basner M, Rao H, Dinges DF. Circadian Rhythms, Sleep Deprivation, and Human Performance. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2013;119:155-90. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00007-5.

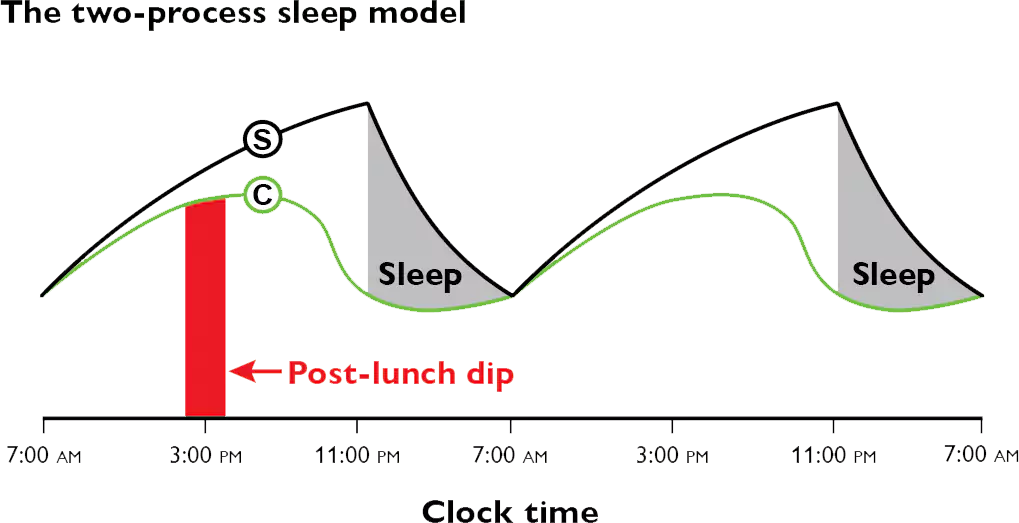

[100] Deboer T. Sleep homeostasis and the circadian clock: Do the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat influence each other’ s functioning? Neurobiol

Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2018;5:68-77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2018.02.003

[101] Borbély AA, Achermann P. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14(6):557-68. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000894

[102] Borbély AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: A reappraisal. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(2):131-43. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12371

[103] Borbély AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1(3):195-204. doi: N/A

[104] Krystal AD, Benca RM, Kilduff TS. Understanding the sleep-wake cycle: Sleep, insomnia, and the orexin system. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74 Suppl 1:3-20. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13011su1c

[105] Franken P, Dijk D-J. Circadian clock genes and sleep homeostasis. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(9):1820-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06723.x

[106] Monk TH. The post-lunch dip in performance. Clinical Sports Medicine. 2005;24(2):e15-e23, , xi-xii. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.12.002

[107] Cajochen C, Chellappa SL, Schmidt C. Circadian and Light Effects on Human Sleepiness–Alertness. In: Garbarino S, Nobili L, Costa G, editors. Sleepiness and Human Impact Assessment. Milan: Springer-Verlag Italia; 2014. p. 9-22.

[108] Posner MI. Measuring Alertness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129(1):193-9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.011

[109] Åkerstedt T, Gillberg M. Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual. Int J Neurosci. 1990;52(1-2):29-37. doi: 10.3109/00207459008994241

[110] Ryan RM, Frederick C. On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. J Pers. 1997;65(3):529-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x

[111] Goel N, Basner M, Dinges DF. Chapter Thirteen - Phenotyping of neurobehavioral vulnerability to circadian phase during sleep loss. In: Sehgal A, editor. Methods Enzymol. 552: Academic Press; 2015. p. 285-308.

[112] Manly T, Robertson IH. Chapter 55 - The sustained attention to response test (SART). In: Itti L, Rees G, Tsotsos JK, editors. Neurobiology of Attention. Burlington: Academic Press; 2005. p. 337-8.

[113] Coulacoglou C, Saklofske DH. Chapter 5 - Executive function, theory of mind, and adaptive behavior. In: Coulacoglou C, Saklofske DH, editors. Psychometrics and Psychological Assessment. San Diego: Academic Press; 2017. p. 91-130.

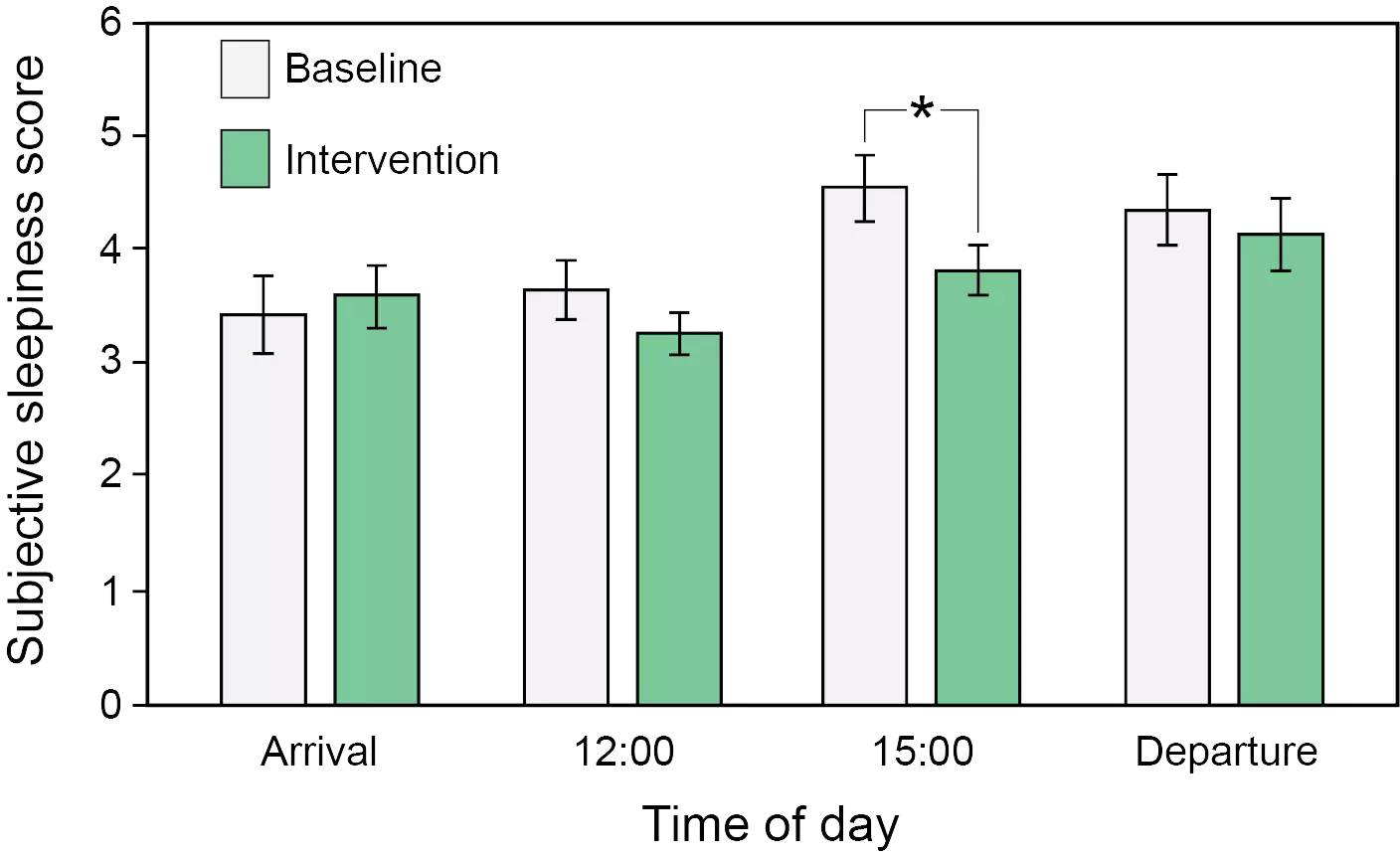

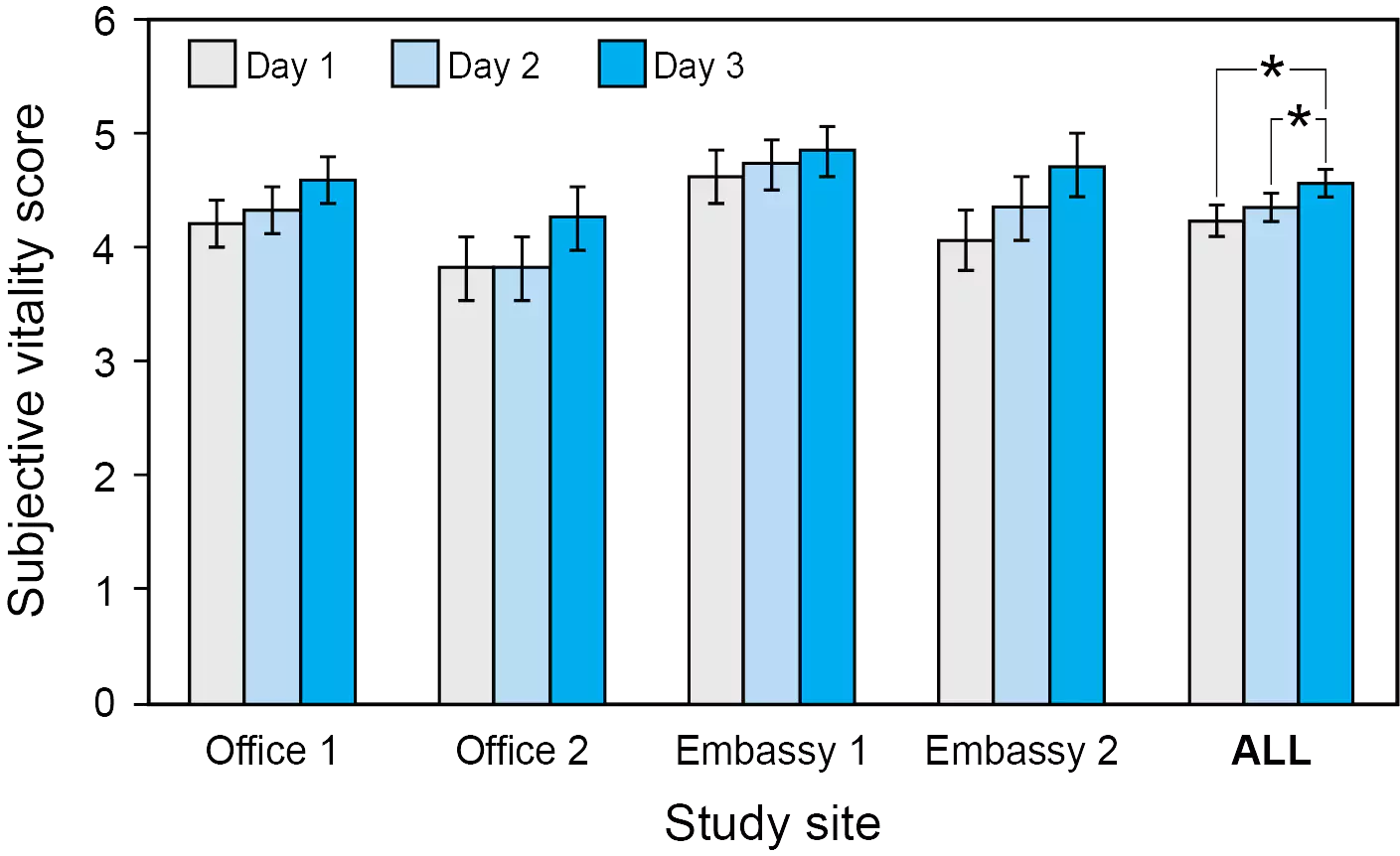

[114] Figueiro MG, Kalsher M, Steverson BC, Heerwagen J, Kampschroer K, Rea MS. Circadian-effective light and its impact on alertness in office workers. Lighting Res Technol. 2019;51(2):171-83. doi: 10.1177/1477153517750006

[115] Figueiro MG, Steverson B, Heerwagen J, Yucel R, Roohan C, Sahin L, et al. Light, entrainment and alertness: A case study in offices. Lighting Res Technol. 2019;52(6):736-50. doi: 10.1177/1477153519885157

[116] Figueiro MG, Pedler D. Red light: A novel, non-pharmacological intervention to promote alertness in shift workers. J Saf Res. 2020;74:169-77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2020.06.003

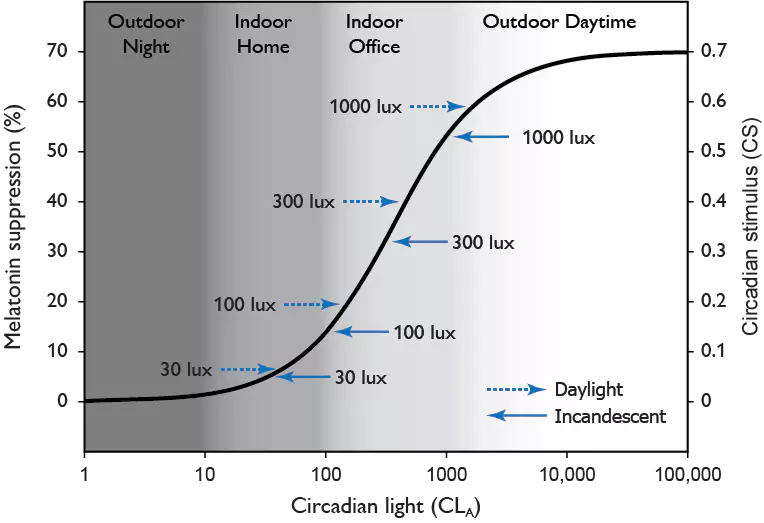

[117] Rea MS, Figueiro MG, Bullough JD, Bierman A. A model of phototransduction by the human circadian system. Brain Res Rev. 2005;50(2):213-28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.07.002

[118] Rea MS, Figueiro MG. Light as a circadian stimulus for architectural lighting. Lighting Res Technol. 2018;50(4):497-510. doi: 10.1177/1477153516682368

[119] Rea MS, Nagare R, Figueiro MG. Modeling circadian phototransduction: Retinal neurophysiology and neuroanatomy. Front Neurosci. 2021;14:1467. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.615305

[120] Rea MS, Nagare R, Figueiro MG. Modeling circadian phototransduction: Quantitative predictions of psychophysical data. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:44. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.615322

[121] Illuminating Engineering Society. Lighting for Hospital and Healthcare Facilities. ANSI/IES RP-29-20 ed. New York: Illuminating Engineering Society; 2020.

[122] Hakola T, Härmä M. Evaluation of a fast forward rotating shift schedule in the steel industry with a special focus on ageing and sleep. Journal of Human Ergology. 2001;30(1-2):315-9. doi:

[123] Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, Carskadon MA, Wright KP, Jr., Vitiello MV, et al. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: Part I, basic principles, shift work and jet lag disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 2007;30(11):1460-83. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1460

[124] Davy J, Göbel M. The effects of extended nap periods on cognitive, physiological and subjective responses under simulated night shift conditions. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(2):169-87. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1391277

[125] Sallinen M, M. H, Åkerstedt T, Rosa R, Lillqvist O. Promoting alertness with a short nap during a night shift. J Sleep Res. 1998;7(4):240-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00121.x

[126] Zion N, Shochat T. Let them sleep: The effects of a scheduled nap during the night shift on sleepiness and cognition in hospital nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2019;75(11):2603-15. doi: 10.1111/jan.14031

[127] Scheer FAJL, Shea TJ, Hilton MF, Shea SA. An endogenous circadian rhythm in sleep inertia results in greatest cognitive impairment upon awakening during the biological night. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23(4):353-61. doi: 10.1177/0748730408318081

[128] Ruggiero JS, Redeker NS. Effects of napping on sleepiness and sleep-related performance deficits in night-shift workers: a systematic review. Biol Res Nurs. 2014;16(2):134-42. doi: 10.1177/1099800413476571

[129] Garbarino S, Mascialino B, Penco MA, Squarcia S, De Carli F, Nobili L, et al. Professional shift-work drivers who adopt prophylactic naps can reduce the risk of car accidents during night work. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1295-302. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1295

[130] Daurat A, Foret J. Sleep strategies of 12-hour shift nurses with emphasis on night sleep episodes. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004(4):299-305. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.798

[131] Schweitzer PK, Randazzo AC, Stone K, Erman M, Walsh JK. Laboratory and field studies of naps and caffeine as practical countermeasures for sleep-wake problems associated with night work. Sleep. 2006;29(1):39-50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.39

[132] Czeisler CA, Moore-Ede MC, Coleman RH. Rotating shift work schedules that disrupt sleep are improved by applying circadian principles. Science. 1982;217:460-3. doi: 10.1126/science.7089576

[133] Golden L. Irregular Work Scheduling and Its Consequences Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2015 [Available from: https://www.epi.org/publication/irregular-work-scheduling-and-its-consequences/.

[134] Lowden A, Öztürk G, Reynolds A, Bjorvatn B. Working Time Society consensus statements: Evidence based interventions using light to improve circadian adaptation to working hours. Industrial health. 2019;57(2):213-27. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.SW-9

[135] Santhi N, Aeschbach D, Horowitz TS, Czeisler CA. The impact of sleep timing and bright light exposure on attentional impairment during night work. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23(4):341-52. doi: 10.1177/0748730408319863